HAMLET — Time is a strange thing. Four hours can seem like four days, and 24 years like seconds.

In the case of Hamlet’s Imperial Foods chicken processing plant fire that killed 25 workers and injured 56, this depends on who and where you were on Sept. 3, 1991.

Calvin White was captain of the Hamlet Fire Department and had just begun his shift.

“We came in that morning, me and the guy I was working with on that shift,” White said. “We got in about 8 a.m. and it was like other days. We started out with some coffee. It was about 8:35 a.m. when the call came in.”

Moments later, White said it wasn’t really a call that came in, but a person. And his name was Brad Roe, and he was operations manager of Imperial on behalf of his father, Emmett J. Roe, the owner.

“Brad Roe came running in our front door saying the plant was on fire,” White said. “What he didn’t tell us was that anyone was inside.”

Not only were there nearly 90 people working in the plant that morning, but the doors meant to serve as emergency exits were locked — from the outside — making escape impossible. Later, it was determined that Emmett Roe had personally ordered the doors to be locked — according to a survivor, to prevent employees from stealing chicken from the plant.

White said that upon arriving at the scene, he called on every fire department in the county to come and help.

“When you do this kind of work, you go into this mode,” White said. “You’re only thinking, ‘This is my job. This is what I do.’ You can’t stop and recognize faces, because a lot of those people we knew. Maybe they were relatives or friends or people we’d helped before or passed on the street. You aren’t looking at them to see if you know them or not. You just see that they are taken care of to the best of your ability.”

Police officers, firefighters and medics live “in a different world from everybody else,” according to White. He said that when you are involved with people on the street — in good situations or bad — it takes a certain kind of person to maintain the objectivity required for those jobs.

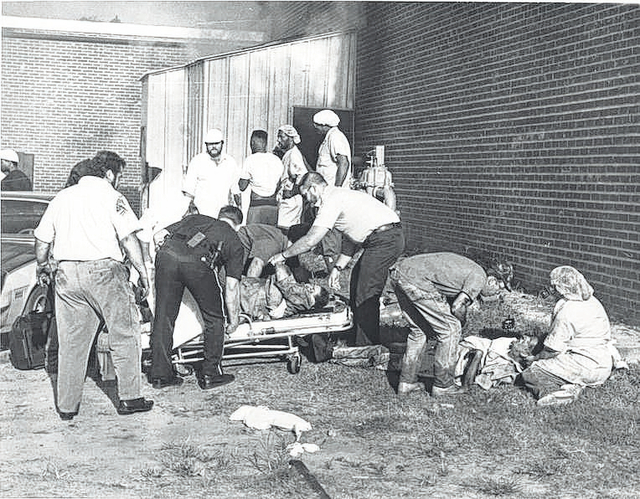

“We had to bring people out,” White recalled. “We had to be as professional with people’s remains as we could. Because those were people and they deserved dignity, we carefully covered those who had passed while the rescue was still on in other parts of the plant. And a lot of people died, but we actually saved lives that day.”

By the time it was over, 25 people were dead and 56 injured. The scene, immortalized in the photographs of Tom MacCallum — then a staff writer for the Daily Journal — remains clearer in the minds of those who were present as first responders, survivors or onlookers. MacCallum, who was also a volunteer fireman at the time, handed his camera to the late Vernon McDonald and joined in the rescue efforts.

White said time seemed very different to him on the day of the Imperial Foods fire.

“It was over in four hours, but it seemed like it lasted for four days at the time,” White said. “It still comes back in waves at times. As years go by they get a little less each time. It comes back, maybe not every day. Sometimes one day, sometimes it may be a week. It might be something I see, or a certain date that brings it all back.”

In 1992 at age 65, Emmett Roe pleaded guilty to 25 counts of involuntary manslaughter, according to the North Carolina Department of Public Safety’s Division of Adult Correction. He was sentenced to 19 years and 11 months in prison but was released only four years later. He was the only one convicted in the case.

“The owner, Emmett Roe, went to prison,” White said. “I’m not sure what ever happened to Brad Roe. I’ve not heard anything about his son for several years.”

White said that as horrible as the Imperial Foods fire was, it changed the state and country for the better.

“Local inspections are much more strict in Hamlet and in the county than they were,” he said.

Lilly Davis, 72 and now living in Laurinburg, experienced the strange undulation of time that day from an entirely different perspective. As one of the victims trapped inside the chicken plant who lived to tell the tale, her description of the events has her stepping in and out of linear clarity.

“When I woke up that morning on the day of the fire, I had said to myself, ‘I don’t think I’m going to work today,” she said. “But I knew there was a holiday coming up and if I didn’t go to work that morning I wouldn’t get paid for the holiday. I was at the plant and had changed into my white coat. Everybody was saying they didn’t want to come to work either. They wanted a longer time off, but if we hadn’t gone in, we wouldn’t have gotten paid for the holiday.”

Davis said the employees went to their departments and got started.

“I went down to the line where the fire happened before it happened,” Davis said. “That was where you weigh the chicken. And my boss man came up and said, ‘I want you to lay out tenders today.’ I told him I didn’t want to go, and he walked off. But then he came back and saw I was still there, put his hands on his hips and gave me this look, so I went.”

Davis explained she didn’t enjoy working with chicken tenders.

“It was always cold in there and those tenders come right out of the refrigerator,” she said. “After a while, your legs feel like they’re not even there. Then all of a sudden the lights went out and we heard somebody yelling, ‘Y’all need to get out of here! This place is on fire!”

Davis said the next thing she knew, the lady who managed the tenders line had gotten everyone to hold hands and told them they would all go out together.

“We were down near the floor and nobody could see,” Davis said. “But we finally got there when somebody yelled, ‘The door is locked! We can’t get out!”

Davis said that’s when the hand-holding stopped. People began to panic, running into other parts of the plant in search of a way out. But it was dark, she said.

“I said, ‘Lord, what am I going to do? How can I get out of here?” Davis said. “And I heard a voice to my right that said, ‘Just sit down right here where you are.’ So I said, ‘What in the world can I do from right here? I can’t see. If only I had some light I could get out.’ And that voice said, ‘You can pray.’”

Davis said she sat down on the floor and began to pray. She doesn’t remember how long she prayed or what she was praying.

“Then a hole opened up in the ceiling,” she said. “I remember feeling so peaceful and good, and then I just fell asleep.”

Davis does not remember anything specific to the plant after that moment.

“I was told by the rescue squad people I was put in a bag and they were getting ready to zip me up,” she said. “But then I coughed once, and that’s the only thing that saved me. I didn’t know anything more until I woke up in Charlotte. My brother was standing over me when I was coming to. He was a preacher, and he and his wife were there. My husband was there, too.”

Davis said she was told she’d been out cold for more than a week. She also heard she’d had a visit from the Rev. Jesse Jackson, who left her a rose.

“There’s a lot that I remember,” Davis said. “A lot that I know. And there’s a lot I don’t remember. But the most important thing I know is I’m alive.”

Gail V. Campbell, her husband’s sister, had not been so lucky.

“She did not make it,” Davis said. “But I really didn’t know they were locking those doors like that until it happened that day. They’d heard someone was stealing chicken so that’s why they locked the door, and I am wondering, ‘Why in the world would they have to lock the doors over that chicken?’”

Davis has been through years of therapy, first as part of the group of survivors and first responders, then later on a one-on-one basis. She said that for a long time after the fire, she was unable to even step outside her door.

“It was like the outside was coming in at me,” she said. “My husband would drive us through Hamlet, but I would get down in the seat and hide like a child. I never could see Hamlet again.”

Davis is now “out of retirement” and working at the Scotland High School cafeteria. She said while she has overcome many scars from the past, she will never forget the day of the Imperial Foods fire.

“As long as I can think right and do things with my hands, I plan to keep working,” she said.

Reach reporter Melonie McLaurin at 910-817-2673 and follow her on Twitter @melonieflomer.